John Dillwyn Llewelyn’s ‘Orchideous House’ at Penllergare; An accidental encounter.

Kevin L. Davies

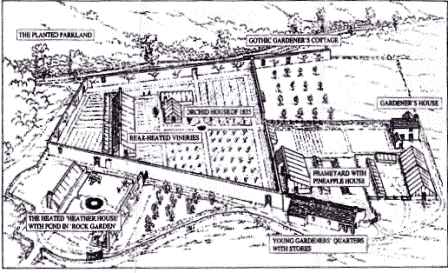

Whilst undertaking a moss and liverwort survey of the Penllergare Estate during the weeks leading up to Christmas 2009, I accidentally came upon the ruins of a complex (Fig.1) which, in its heyday, consisted of a gardener’s house, apprentice gardeners’ quarters, frame-yard with pineapple house, a walled garden with rear-heated vineries, a heated heather house and a rockery with pond. In the midst of the walled garden stood the remains of a building that I immediately recognized as John Dillwyn Llewelyn’s ‘Orchideous House’, dating from about 1843 (Fig. 2). It had always been an ambition of mine to visit the site, but I had been discouraged by the reports of all those who had already attempted to do so. Access, it seemed, would be difficult and dangerous on account of the dense vegetation and terrain. This may well be the case at the height of summer, but it was certainly not my experience on a cold, winter’s afternoon, when much of the vegetation had already been hit by frost and had died back revealing the stonework and exposing bare soil.

Fig 1 – The garden complex at Penllegare

It was the contrast between the few features that I had anticipated finding there (based on other people’s photographs) and the extent of the ruin which met my gaze that made the most impact on me. So well preserved were many of the details, that they could be compared directly with the plan of the glasshouse published in the Journal of the Horticultural Society Vol. 1 of 1846, and reproduced on this website in Richard Morris’s article. Against the ivy-clad gable end could be seen part of the triangular, brickwork flue, behind which would have originally stood the boiler and coalhouse (Fig. 2). At its base still stand several massive boulders that would originally have been part of the waterfall that John Dillwyn had built, having being inspired by Robert Schomburgk’s 1841 account of his visit to the Essequibo River, Guiana, where he had seen and described the “splendid vegetation which borders the cataracts of tropical rivers”. The profile of the cistern, into which the heated water would have cascaded, can still be seen, and this extends from a short distance within the entrance to the aforementioned boulders.

Fig 2

Along the sides of the stove house run the remains of staging constructed from brick and slate, beneath which occur holes. Through these would have passed the hot water pipes, essential for maintaining the health of newly imported orchids in the cold, Welsh climate (Figs 3-4)

Fig 3

It seems that Sir John Talbot Dillwyn Llewelyn, elder son of John Dillwyn, following his father’s demise, used the, by now, somewhat derelict orchid house to propagate Camellia seedlings, and the old cistern was promptly converted into a raised bed, complete with a surrounding brick wall that can still be seen (Figs 2-4). Indeed several mature camellias grow close to the orchid house, having survived from the time that Sir John lived at Penllergare (Figs 3-4).

Fig 4

In short, the old ‘Orchideous House’ at Penllergare is still well worth a visit, if only to imagine how it would once have appeared in all its glory. However, if you wish to avoid thorn-torn arms, legs and clothes, do plan your visit for winter.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Richard Morris for allowing him to use the illustration of the walled garden complex and Dr. Isabella Brey for taking the photographs.