A. Raymond Walker

Motley’s Orchid – Coelogyne motleyi

(Photograph – C.L. Chan)

Research into the life of James Motley has been particularly difficult because all his records were destroyed in Borneo when he was killed in 1859. His life as a young man in South Wales is not well documented and no family letters or photographs have yet been discovered. He arrived in South Wales from Leeds in about 1840, when he was 18 years old, and his first home may have been somewhere near Aberavon. Here he trained as a mining engineer and surveyor, possibly starting as an apprentice in one of the coal mines nearby. Unfortunately, we do not know where.

The dates stated throughout this article are based on the best existing references, but they are still subject to scrutiny. His prowess as a naturalist is better documented. James Motley was a prodigious collector and recorder of natural history items. His life can he separated into two entirely different categories: life in South Wales and life in Borneo, where he went in 1849. Thanks to his letters from Borneo to Sir William Hooker and his friendship with Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn we know a considerable amount about his adventures in South East Asia. James Motley died when he was one day off being 37 years old.

A brief account of the Motley family in South Wales

The Motley family originated from the Leeds area, where there are many branches dating as far back as 1582. A preference for the Christian name of Thomas and James, without a second name, has caused a great deal of confusion. There are, for instance, fourteen people listed as Thomas Motley for that region in the l6th century.

Thomas Motley married Caroline Osborn at St. Peter’s Church in Leeds on 10th January 1820. They had six children. James Motley was the eldest and was born on 2nd May 1822. He was christened at St. Peter’s on 25th May 1822. They lived at East Parade, Osmondthorpe in Leeds. He was educated at St. Peter’s School, York, under the Rev. Mr. Creyhe (later Archdeacon) and then, at St. John’s College, Cambridge. He originally intended to study for the church, but chose civil engineering instead, with the intention of helping his father in his various businesses.

By the late 18th century, the South Wales Iron Works industry was fast becoming the largest in the world. The Maesteg Ironworks attracted a number of English investors in the early 1800s; this included Thomas Motley from Leeds, Henry Fussell from Warminster and William Buckland from Reading. They also invested in a new company, the Dyffryn Llynfi and Porthcawl Railway Company. By 1828, the blast furnace in Maesteg and the Railway were in operation. In the 1830s, the Maesteg works had closed links with Robert Smith & Company of the Margam tin works. When Smith died, the original investors traded as Motley, Fussell and Company from 1841 to 1843, owning both the Maesteg site and the Margam tin works. There were 500 workers in Maesteg and 396 in Margam. These were indeed big investments.

There were large profits to be made, but unfortunately, there were also risks involved due to over-production and violent fluctuation in the price of iron. These factors may have led to the eventual failure of the companies and both were advertised for sale in the Cambrian newspaper on 4th April 1843. They were not sold for six years, and iron production was not started again until 1852 at the Maesteg Company.

Thomas Motley must have moved his family to Wales in about 1840; but he must have been a frequent visitor to the Principality before this, taking with him his eldest son and leaving his family at home in Leeds. James Motley recorded most of his South Wales plants between 1840 and 1848, when he was botanising Glamorganshire and Carmarthenshire. There are, however, earlier records showing he was in Merthyr Mawr in 1834.

For some unknown reason, Thomas Motley then invested in a new Tinplate manufacturing works at Dafen in Llanelli, built from scratch between 1845 and 1848. His partner was a retired surgeon-dentist from Bath, Mr. John Winkworth, and James Motley was also made a partner. It is difficult to assess the part that James may have played in the construction of the works. It was built inland and as lots of water is essential to Tinplate manufacture, a stream was diverted to form a large pool (which still exists today). Coal was to be the major fuel source and there was an existing coal mine near the site. James Motley may have been involved in preliminary work. He was already an experienced surveyor but I doubt that he had any major involvement in the project. Byron Davies, a Llanelli historian, has written authoritatively about the history of Tinplate in Llanelli. He concluded that Tinplate may never have been produced in Thomas Motley’s time, but forged iron was – this being an integral part of the whole process.

About 1843, Thomas Motley, with his family, moved to Ael-y-Bryn, a large house at Felinfoel, near the factory. James Motley may also have lived there for a time as there are plenty of plant records by him from this area. This house, much enlarged, still exists as the Diplomat Hotel and is one of the Best Western Group of hotels.

Aelybryn – the house in Felinfoel, Llanelli where Thomas and Caroline Motley lived around 1846 – 1848.

(Photograph by A.R. Walker)

Later in 1848, Thomas Motley moved to Rock House in Pembrey, but now only with his wife and two daughters, Sarah and Sophia Osborn. Unfortunately, Thomas Motley over-reached himself and was declared bankrupt. In January 1849, he wrote to his landlord stating that he could not yet pay the rent, “My distress is at present very great, and almost overwhelms me”. The Dafen Tinplate site was sold, probably way below its true value. Soon after, Thomas Motley, his wife and two daughters went to live in the Isle of Man, possibly to avoid his creditors.

Rock House in Pembrey where Thomas Motley moved in 1848.

He lived until he was 81 years old and may have been aware of the eventual success of the Tinplate industry, started by him in Llanelli, despite successive booms and failures. After several owners, it eventually closed in 1958, after 112 years, thereby ensuring that the name of Motley has a prominent place in Llanelli’s history.

Thomas Motley died in the Isle of Man in 1863, followed by his wife, Caroline, in 1869. Their daughter Sarah,married William Stothort (junior) in 1856, but she died in 1860 and was not buried on the island. Sophia Osborn married Richard Mason and died in 1922, at the age of 88.

An individual named Thomas Motley (born 1791) was active in the Bristol area at the same time that our Thomas Motley came to South Wales. I had for a time considered this to be the same man, but this is not the case. He and his son, also Thomas Motley, were architects and engineers and built a suspension bridge at Tiverton near Bath, which is still known as Motley’s Bridge. As far as I can ascertain, these had no direct relation to the Motleys in South Wales.

There is much less information about Arthur Motley, James’ younger brother by two years. He also came to South Wales with the family, but seemed to develop a separate career for himself. Despite just one dubious reference to his connection with his father’s Tinplate factory, I think he kept well clear of his father’s problems.

Arthur Motley married a widow, Jane Fredreca Boye (née Bowman) on 22nd July 1847 and, in the census of 1851, he was living in a house called the ‘Sanctuary’ at Loughor. This house, in Castle Street, still exists and has a long history going back to medieval times. Arthur Motley aged 27, is listed as an agent at the Copperworks. Besides his wife listed in the census of 1851, there are two children listed therein (two more were born later) as well as his wife’s daughter by her former husband, his wife’s mother and three sisters. There was also the wife’s brother, a visiting analytical chemist and two servants, thirteen people in all. Fortunately, it was a very large house.

James Motley also stayed at the Sanctuary and was married to Mary Susanna Bowman at nearby Loughor Parish Church on 12th February 1849. On his marriage certificate, James Motley is listed as ‘mineral surveyor’ and said to be living in the Parish of Ystradgynlais (there were anthracite mines nearby). The marriage was witnessed by the bride’s father Joseph Bowman and Francis Motley, who was the third and youngest son of Thomas Motley.

Francis Motley does not seem to have lived in South Wales and may have stayed in the Leeds area with another family (there is evidence the Motleys took care of children from other families!). It is known that Francis (born 1826) went to Burma where he married a Bengalese lady and had three children. In the 1871 census, he was in Horsforth near Leeds, having retired and owned a firm manufacturing galvanized iron. It is a notable fact that Arthur and James Motley both married Bowman sisters.

It is recorded that James met Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn in London on 18th February 1849. Mr. and Mrs. Motley must have travelled to Borneo soon after this.

After the 1851 census, Arthur Motley seems to have disappeared. In fact, he emigrated to New Zealand. There are records in Leeds Museum (1860-61) of gifts by him of various items from New Zealand including rocks, minerals, Celts and a Mario Maori head. I do not know the subsequent history of Arthur Motley.

Plant collecting in South Wales

My interest in James Motley began with re-boxing and packing his collection of plants which is housed at Swansea Museum. There are 461 pressed plant specimens which he gave to the museum in 1848, prior to going to Borneo. It is now incomplete and there are some mixing with wild plants collected by James Ebenezer Bicheno (1785 — 1851). This man also gave his collection of plants to Swansea Museum in 1842, before he went to Tasmania as Colonial Secretary. Motley and Bicheno I am certain were very good friends.

Motley’s collection was very varied. One hundred and thirty-three specimens were from the north of England, some from his previous home in Osmondthorpe (about 33 specimens), but also from all over England and Scotland, one from Ireland and some from Jersey. Motley never went to these last places and would have received them through his contacts with other botanists. Three plants were from Henfield near London. This was the home of William Borrer (1781 — 1862) who was known to be another friend of Motley and they botanised together in Wales. The Rev. H. J. Riddelsdell reviewed the Swansea herbaria of Bicheno and Motley in ‘The Naturalist’ of 1903. He was complimentary about the accuracy of Motley’s identifications. The plants that Riddelsdell reviewed were only from the North of England. There is an unpublished recent list by G. Hutchinson (1999) which summarised Motley’s findings but a list of Carmarthenshire plants, which Motley most certainly made, has unfortunately been lost!

By far the most accurate account of James Motley as a botanist in South Wales is that by Ian Morgan. He describes him as a polymath, but regards him as a pioneer botanist in Carmarthenshire. Ian Morgan’s article in the Llanelli journal Tinopolis of 1995 lists many of the interesting plants found by Motley. For example Wilson’s Filmy Fern (Hymenophyllum wilsonii) was found in the Lliedi Gorge opposite Ystradfair, but the site is now a reservoir. Flix weed (Descurainia sophia), recorded by Motley, was rediscovered by Ian Morgan in Pembrey.

On one of his earlier visits to Glamorganshire (1834), Motley records as, “When quite a boy” (he was 12 years old at the time) finding Purple Spurge (Euphorbia peplis) abundant on “Porth Call” (sic) sand hills. On a re-visit in 1841, the plant had gone. Motley was a member of the London Botanical Society and several of his records were published in the Phytologist, a botanical journal. Despite his youth, he was expert enough to have identified a number of unusual plants. James Motley contributed substantially to what was then known of wild plants in South Wales and indeed, his records of rarer plants, now disappeared, are of particular interest to present-day botanists.

James Motley’s publications

James Motley was also interested in Welsh culture. In 1848, he published a small book entitled Tales of the Cymry, with Notes, Illustrative and Explanatory. This was Motley’s book on Welsh heritage and legend, and was a study of several traditional poems which were printed in the book in English. There was additional information on history and pre-history, for example on Arthur’s Stone in the Gower. In 2004, a copy was sold for £50.

The Natural History of Labuan and adjacent coasts of Burma, Volume 1. was published in 1855 by J. Motley and Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn. The book was a co-operation between Motley, who sent the specimens and detailed the observations, and Dillwyn, who arranged the publication through his printer John van Voorst, who also arranged for production of very good quality, hand-coloured plates from Motley’s preserved specimens. The book sold for 10 shillings and six-pence (521/2p).

The preface of the book states that further volumes would be produced, two or three annually, each with 12 plates. Volume 1 contained details of 49 birds, 16 lizards and snakes and 10 mammals. Further volumes, it stated, would contain, “Vertebrates and Invertebrates of fauna little observed”. Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn probably became otherwise employed. He became MP for Swansea in 1854, a post which he held for nearly 40 years. He was also, undoubtedly, paying for the cost of production. No more volumes were published.

In 1852, Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn gave a lecture to the Royal Institution of South Wales on Labuan, using what he called “Material from my friend resident in Labuan”. There is a written copy in Swansea Museum, but it was never published.). One story he tells is of a Chinaman who had dysentery. Motley treated him for three days with laudanum (opium), calomel (this contains mercury) and quinine. Surprisingly, the man got better.

James Motley in Borneo

About March of 1849, James Motley travelled to Borneo. Previously samples of coal had been sent to Henry De la Beche from Labuan and he pronounced them, “as good as Newcastle”. I think there is no doubt that it was his influence that helped Motley to get a job with the Eastern Archipelago Co. (trading 1849 — 58). Motley’s experience as a coal mining surveyor in South Wales was to help him develop mining on the island of Labuan, off the North West coast of Borneo. At first, surface coal was mined, then underground, probably using drifts. Motley was in charge of these operations. The British were keen to open up a naval base at Labuan, which they did in 1846. The island, which is about 8 miles across and about 5 miles from the mainland, was probably unoccupied until this time. The naval base was intended to control piracy and develop coal supplies for passing ships.

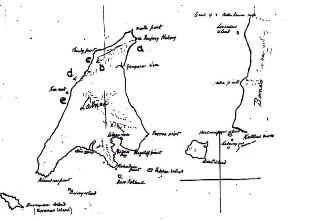

A drawing of Labuan Island by James Motley showing where coal was being mined.

Labuan Island as it is today. Coal-mining ceased there in 1858 but it is now a major exporter of petroleum gas.

In Borneo, James Motley would be introduced to an extraordinarily diverse number of tree species. Here were to be found dipterocarp jungles and these can sustain over 500 species of tall trees, as well as different levels of sub-canopy vegetation.

On arriving in Labuan, I am quite certain James Motley had not realised the difficulties he would have extracting the coal. The island was entirely covered in jungle, some trees were 45 metres high (150 feet) and the jungle had to be cleared. Motley’s operations were mainly in the north of the island, “6 miles from any white-man”, he said. There were, as yet, no roads and Motley travelled by boat along the coast from the main settlement in the south called Victoria (now called Bandar Labuan).

Motley found Labuan an unspoilt botanical paradise. From his letters to Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn, he was obviously overwhelmed by the jungle and its animals and birds. (Today the jungle on Labuan has been almost entirely cleared.)

What seemed to be an encouraging start in Labuan, soon turned into a disaster for Motley. To control six different nationalities and to learn their languages was difficult enough, but he was soon complaining bitterly about his employers. His managing director hardly ever visited and instead, travelled in China and Asia. Then a strong-box in his charge was broken into and a substantial amount of money was stolen. Motley complained of overwork and requested a substantial pay rise. He wanted an agreement of £1,000 for two years, but this was refused. In fact four mining companies went bankrupt in Labuan in quick succession, from incompetence as much as bad luck! It was not helped by the fact that Welsh coal was being sold in Hong Kong for £1-17-0 (£1.85) a ton. Labuan could not compete with this.

Motley wrote a very apologetic letter to Hooker, saying that he had been reported for owing money. A summons had been issued against him and the contents of his home had to be sold, including two decorated Malay swords and collected specimens, for which Motley complained he only got 5 dollars. (These plant specimens did eventually get to Hooker.)

From Labuan, Motley described how he could see a mountain in the distance on the mainland to the North East, stating. “In the mornings, it seemed a person might suppose it to be within a day’s walk”. This, he said, was called Keeva Baloo and was about 16,000 feet high and about 90 miles distance from Labuan. In fact, it was Mt. Kinabalu and is 4,101 metres high (13,455 feet) and is about 250 kilometres (140 miles) from Labuan. It is the highest mountain in South East Asia (that is from the Himalayas to the high mountains in New Guinea). Mt. Kinabalu and the area around it in Borneo, subsequently, became one of the most famous national parks in the world.

Hugh Low (1824 — 1905) was Colonial Secretary in Labuan when James Motley arrived in 1849. He was previously treasurer to Sir James Brooke (later called Rajah Brooke) who consolidated North Borneo for the British. Labuan was British from 1846. Hugh Low was appointed in 1848 and stayed until 1877. He was also a botanist and must have known James Motley, but none of his letters mention him nor is there any record of a dialogue between them.

Hugh Low was the first European to climb Mount Kinabalu in 1851, with 42 porters. This involved a trek through dense jungle for 60 miles (100 kilometres) to the base of the mountain. Low collected rare orchids and pitcher plants on the way.

A frustrated Motley wrote, “I have never yet been able to get a holiday in the mountains, if I could only get away to some 5,000 or 6,000 feet above the sea where I could really do a day’s walking”. He never did visit Mt. Kinabalu, but he did briefly explore the mainland opposite the island of Labuan, despite objections from Rajah Brooke.

Today there is a road to the base of the mountain and, together with the adjacent area, it forms the Kanabalu National Park (753 square kilometres) and has over 200,000 visitors per year. It is an outstanding example of prime jungle, known for its rare birds and plants. There are many endemic species, including 1,200 species of orchid and 220 species of birds. Unfortunately, Motley’s achievements were overshadowed by Hugh Low who was an outstanding botanist and naturalist. Motley did not enjoy Low’s privileged position. If they had formed a better relationship, Motley’s traumatic future may have been very different.

On the 18th December 1853, James Motley wrote to Hooker saying that he was now in Singapore and had left the company for which he worked. By now, he had two children and, for about a year, had not had a job. He travelled in Sumatra and Java and used his time to explore. His letters of 1854 describe horrendous journeys to Sumatra in an unseaworthy Sampan. He was exploring the many islands in the Molacca Straits between Malaya and Sumatra, including the island of Putan Lingea and the River Indragiri in Sumatra. Once, when in one of the estuaries, a large tree floated down the river and nearly sank their boat.

It is difficult to envisage how Motley and his family managed between jobs. He did say in his letters he could not afford to come back to Britain and the climate in South East Asia suited them both. He did, however, do some surveying work in Sumatra and there is a record in Lewis Llewelyn Diliwyn’s diary of a £30 loan to Motley in 1854. He may well have helped him further.

He visited Java twice and journeyed to Batavia to explore the possibility of a new job with a Dutch mining company. While in West Java, he visited the Pangrango Highlands which has a peak of 3,019 metres (9,960 feet). The area is now the National Park of Gede Pangrango. He also visited the Kebun Raya Botanical Gardens, 50 kilometres from Batavia, which had been opened by the Dutch in 1817.

Motley stayed with Dr. Burger of the Netherlands India Mining Company in October 1854 and then proceeded to Banjarmasin in South East Borneo. The site of a new coal mine was to be 28 kilometres (about 16 miles) from the coast and Motley was to be the superintendent of mining for that area.

In the four years he spent in South East Borneo he seemed happy. He now had three children, although the names, ages and gender are not known. Motley wrote to Hooker that he had received applications from Calcutta, Sydney, New York and New Orleans asking for specimens, so many he could not answer. One German correspondent, Motley said, “Had the coolness to ask for a vocabulary of native dialects”, a request he had no intention of fulfilling. He said he spoke English, French, Malay and Dyak every day. He was also learning Dutch, also Japanese, Chinese and Bengalese could be heard. Motley likened it to the Tower of Babel.

Motley also sent letters to Henry De la Beche with technical details of the coal that he was mining. A coal mine was established after 100 borings and Motley said he was never without his theodolite. He was interested in fossils (as these were a help in identifying the coal seams) and he describes collecting 200 late tertiary coal fossils. These were sent back to Britain, but cannot be traced in any museum now. Earlier collections of fossils were given to Leeds Museum. Motley said that he was writing an article for the Society of Natural History at Batavia, of which he was a member. He found difficulty getting the coal to the coast as the rivers were unreliable for boats. He describes the country as similar to the fens of East Anglia, but also with extensive jungle. As a result, Motley built a new canal several miles long to facilitate the export of the coal. This shows that he was also a skilled engineer.

He was very proud of his garden, which he said was very beautiful. It contained over 150 species of orchid, 26 species of palm and many species of Hoya. He said he had only to hang plants on the garden paling for them to grow and flower.

Plants in Borneo

James Motley’s paramount interest was botany. He collected over 2,000 plants in Borneo. William Hooker received these at Kew and distributed them to whatever specialist was dealing with that plant family. Specimens would be compared with other collections and Motley’s plants often proved to be new species. These were given a name and the ‘type specimen’ kept at Kew for permanent record. Specific names would often incorporate Motley’s name. For example, the specific epithets motleyi and motleyanum occur 80 times and the genus Motleyia belongs to a plant from the coffee and quinine family (Rubiaceae). One small water lily, some 15 to 30 centimetres (6 to 12 inches) high, occurred in jungle pools and in 1858, Motley sent this plant to Hooker, complete with a full description in Latin and a sketch. Hooker called this plant Barclaya motleyi Hook. This was his way of honouring Motley because, by the time he came to name this plant, he knew that Motley had died. Hooker in fact named quite a number of Motley’s plants. Naming plants and animals after people who first found them is now discouraged.

James Motley did not confine himself to flowering plants. He had 14 ferns (pteridophytes) named after him. Motley informed Hooker that he was sending cryptogam specimens (non-flowering plants) to William Mitten (1819 — 1906) at Hurstpierpoint, Sussex, as he was a specialist in bryophytes (mosses and liverworts). A search by the author for Motley specimens was not entirely successful, but he did discover that some of his herbarium specimens still at the Natural History Museum in London and at the New York Botanic Garden. One species of moss, Calymperes motleyi from Labuan was named by Mitten, and there must be others in various herbaria.

James Motley was very interested in trees, and the extraordinary number of species in the jungles of Borneo must have occupied his time. Motley described some of the trees that he felled in Labuan to get to the coal seams. One enormous tree of Dryobalnops aromatica was called the Borneo- or Sumatra Camphor tree. This one tree measured 1,350mm (4 ft 6 inches) in diameter 15 feet (4.5 metres) from the ground. It had enormous radiating buttress roots 100 metres (330 feet) around and a platform had to be built to cut into the bole. The tree was about 40 metres high (130 feet). He also described another Camphor Tree, Cinnamomum camphora, which he describes as producing about 20 litres (5 galls) of oil.

Motley was also interested in the practical use that could be made of jungle trees. He sent notes to Hooker, with plant specimens and the wood of the Camphor Tree. He had the white crystals found in the wood analysed by a chemist. Hooker wrote a paper on this tree based on Motley’s observations, which was published in Journal of Botany and Kew Garden Miscellany Vol. 4., 1852. The Chinese used the oil from this tree as an embrocation. It was from this that camphorated oil and the original moth balls were produced. The flowers were white and deliciously scented, whereas the fruit, though smelling of turpentine, was greedily eaten by a small parakeet.

In March 1858, Motley sent a box of 103 specimens of wood to the museum at Kew. These were all numbered, and the trees described. He also wrote about the uses of the wood produced by a certain species of tree, and whether it could be used as planks for building purposes, or furniture, or the sheaths of knifes etc. He also added the native name given to the tree. Another tree which interested Motley was the Gutta Percha tree (Palaquium sp.) He sent specimens and sketches (not traced) to Hooker, and these included a new species. This tree produces a rubber-like substance which was extensively used until rubber became more available. When Motley got to Singapore he was quite interested in becoming an exporter of ‘gutta’. He foresaw opportunities here, but admitted he did not have the money to start. He was quite right correct. By 1920, the value of gutta exported from Singapore had increased to 8 million dollars. Until I read Motley’s letters, I had not realised that he had also sent back a large number of ethnological items, such as a hat made from rattan, sleeping mats and a wood used as an aromatic soap. There was also cordage, clothes, medicines, dyes and arrows made from a wood called Alstonia, and this included a phial of a lethal poison made from bark into which arrows could be dipped.

Birds and animals in Borneo

Motley did not show a great interest in birds until he went to Borneo, where he was obviously enchanted with what he saw. He describes in his book (Motley & Dillwyn) the Copper- Throated Sunbird (Nectarinia calcostetha) feeding on a coral plant outside the window of his office. This plant has long, tubular, scarlet flowers and the bird hovers in front with its long tongue sucking up the nectar. James Motley said he had never seen anything more beautiful than this plant with several Sunbirds feeding on it.

He also records that Mrs Motley reared a young Orange-billed Flower-Pecker (Dicaeum trigonostigma) on rice and banana pulp. At one state, he kept an Oriental Pied Hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris) in a cage. This bird is about 21 inches long (525 mm) and Motley said it would eat almost anything.

Motley sent about 200 bird specimens back to Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn, of which 49 species were described in his book. Motley is credited with making the first list of Borneo birds. The list is valuable because of his observations on the habits of these birds. One example is the Philippine Scrubfowl (Megapodius cumingii, Dillwyn 1853). Based on Motley’s descriptions, it was named by Dillwyn. It is a Megapode or Mallee Fowl, and characteristically, these birds do not build nests. They lay their eggs in an enormous pile of sand and rotting vegetation which acts as a giant incubator. Motley said that natives found the eggs good to eat. He also described the Malays trapping the birds by building low fences on the floor of the jungle. As the bird tends to run, rather than fly, it is caught in the fence gaps.

The Black-headed Munia. The first colour picture of this bird was in a book by Motley and Dillwyn, published in 1855.

(Picture by permission of Swansea Museum)

Several birds recorded by Motley were new species. The endemic, White-Crowned Shama (Copsychus stricklandii) is one named by Motley and Dillwyn in 1855. In 1863, Sclater analyzed Motley’s contribution, which added 58 species to the Borneo list.

Motley invariably killed birds when he wanted the specimen for identification, but they were also killed for food. He describes how he shot through the neck a Grey Heron in Sumatra (1854). His servant cut slices from the breast and legs and cooked them. Motley said that they tasted like Woodcock.

Scaly-crowned Babbler – also illustrated in the book by Motley and Dillwyn, published in 1855

(Picture by permission of Swansea Museum)

James Motley was a good all-round naturalist. In the paradise of wildlife that he found in Borneo, he collected mammals (including bats), birds, snakes, lizards, shells and some insects. He said that at one stage he was asked to collect lice from birds and mammals.This, he disliked intensely. Some birds and snakes were new species. All would be skinned, preserved and sent to Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn, who sent them on to various places, including Leeds Museum. They were so pleased at the collections sent them that they made Dillwyn an honorary life-member of their society. The 19th century collectors seemed to have no conscience about killing animals.

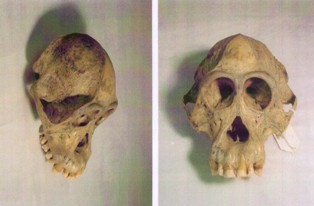

Motley kept a Pangolin (Manis javanica), a type of scaly ant eater, as a pet, but eventually killed it and preserved its skin. Its flesh was cooked and eaten by Japanese sailors. He was particularly interested in the Orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeus), as it had only recently been identified as a primate endemic to Borneo and Sumatra. Museums were clamouring for specimens and James Motley sent back at least three skulls and skins of Orang-utans. These animals had probably been killed by a native hunter that he had employed in South East Borneo to collect specimens for him. Motley thought that there were three species, but this was not the case.

Orang-utan skulls in Leeds Museum. They may have been collected by James Motley.

Did Motley ever meet Alfred Russell Wallace? There is no record of the two ever meeting. They were both in South Wales about the same time (1841 – 1848), and both contributed to Lewis Weston Dillwyn’ s book Materials for Fauna and Flora of Swansea, which was written for Swansea’s British Association meeting in 1848. Lewis Weston Dillwyn was an eminent botanist and father of Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn and John Dillwyn Llewelyn. Wallace contributed towards a list of beetles, and Motley a list of plants (69 species). Wallace collected a phenomenal number of insects (about 25,000) in Borneo while he was a guest of Rajah Brooke in Sarawak (1854 -1856), but at that time, Motley was about 600 miles away in South East Borneo and would have had no opportunity of meeting him.

Wallace also collected Orang-utans, and killed about 16 of them. One female was found to have a very small baby which clung to Wallace’s large beard. Unlike Motley, Wallace sent his specimens back to his agent in London for sale!

It is of some significance that none of the bird or animal specimens in museums can be identified today as being collected by Motley. Leeds Museum has two Orang-utan skulls which may be those sent by Dillwyn, but it is not certain. Perhaps Motley’s taxidermy has not been good enough to stand up to the passage of time (150 years).

Conclusions

In 1859, James Motley must have been pleased that he was now established in South East Borneo, at Kalangan. He was superintendent of a private coal mine called Julia Hermina, which he had established, and which was now producing coal. His collecting was going well and he had just sent 1300 plant specimens off to Hooker.

There were rumours of unrest, but Motley had written to his father in the Isle of Man on 18th April 1859, assuring him that there was no need to worry. Twelve days later, he was dead. The reigning Sultan of the area was unpopular and there was a conspiracy against him by his brother. This culminated in a full-scale war against the Dutch, which lasted until 1863. The Dutch authorities blamed their representative at his court for not warning them in time. Moslem insurgents had rallied the Dyaks and other natives to rebel and, no doubt, the Dyaks did most of the killing. The first attacks were on 28th April 1859 at Pengaron. The Dutch overseers were killed, but a Mr. Wymalen returned to his house with his family and defended himself. After three hours, the house was set on fire and all were killed, including four children. James Motley was killed on 1st May 1859, at his place of work. At first, it was hoped that his wife and three children had escaped, but when a small force under Colonel Anderson reached the area three to four days later, he reported that all the white people had been killed. In other areas, four missionaries, their wives and 19 children had been killed. Everything was destroyed, the house, the coal mine and all their possessions, including Motley’s collections. Over 100 white people must have been killed and it was years before the Dutch re-established themselves in the area. Local mining in this particular part of the country was never re-commenced.

This is a reduced account of James Motley’s life based on an article by A. Raymond Walker in the Swansea Historic Journal 2005, Vol. XIII, also known as Minerva. This account includes additional pictures, information and maps. Most of the information has been obtained from Swansea Museum and it is with their permission that it is reproduced. Further information has been obtained from Kew and other archival sources.